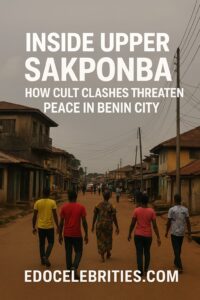

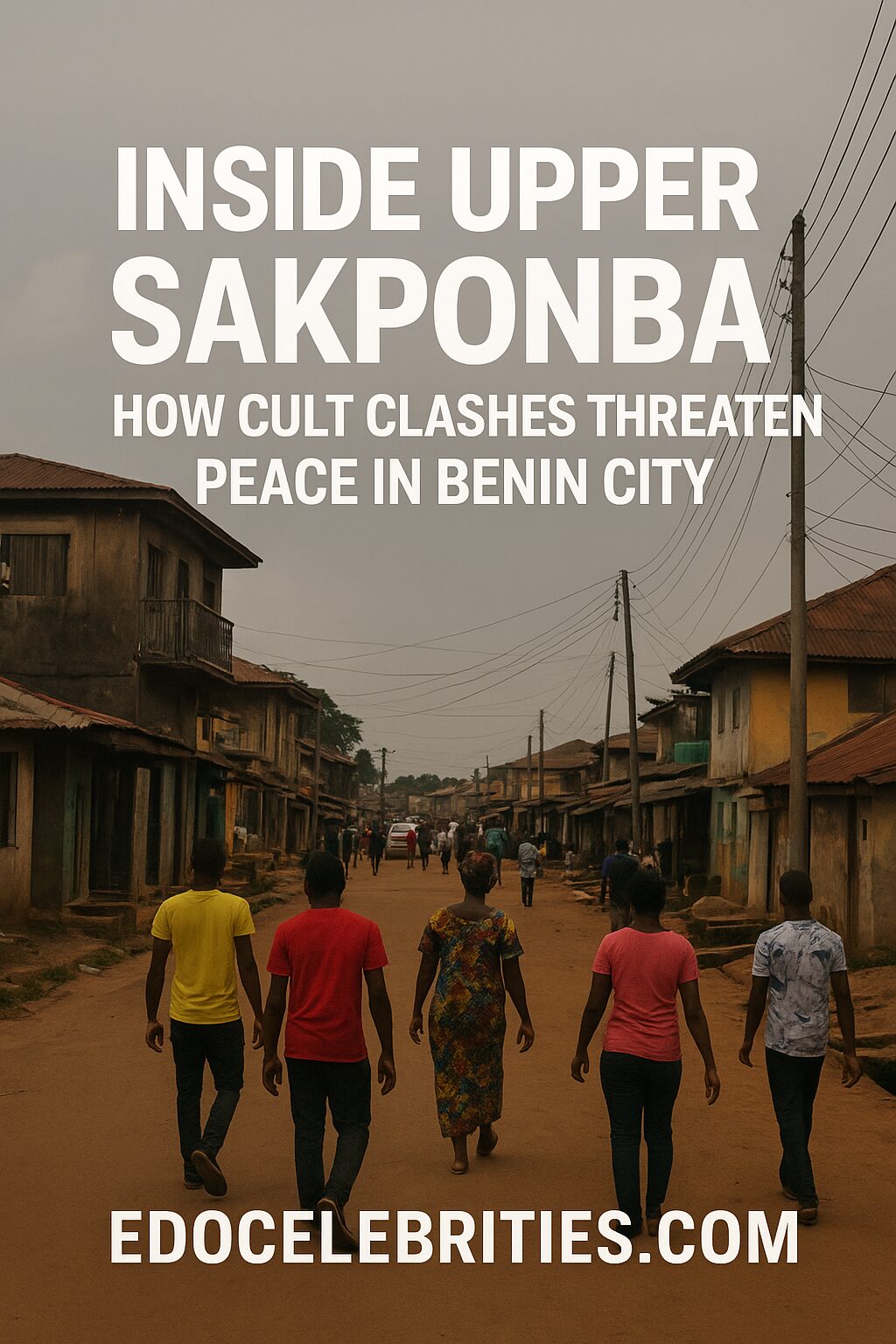

For years, Upper Sakponba, one of the busiest corridors in Benin City, Edo State, has been at the center of violent cult clashes that have claimed dozens of lives, displaced families, and shattered the once vibrant community’s peace.

Once known for its bustling markets and thriving motor parks, Upper Sakponba has gradually turned into one of the most volatile neighborhoods in Southern Nigeria, with residents living under constant fear of reprisal attacks and police raids.

At the heart of this crisis lie deep-rooted issues — youth unemployment, political manipulation, and a failing security structure that has left ordinary citizens trapped between armed gangs and ineffective policing.

The Rise of Cult Violence in Upper Sakponba

Cultism in Benin City isn’t new — but in recent years, Upper Sakponba has become its epicenter. Rival groups like the Eiye, Aye (Black Axe), Vikings, and Mafia reportedly battle for territorial control, extortion points, and political influence.

Residents describe a grim pattern: sudden gunfire at night, hurried closures of shops, and corpses left on the roadside by dawn. During clashes, even commercial tricycle riders abandon the streets as businesses shut down and schools remain empty.

Security sources link many of these cult groups to political patronage, noting that some gangs receive funding and protection from local politicians during election periods. When elections end, these same gangs often turn their weapons on one another in power struggles for dominance.

The Role of Youth Unemployment

A major driver of cult recruitment in Upper Sakponba is joblessness. According to Edo State’s 2024 statistics bureau, unemployment among youths aged 18–35 remains above 38%, one of the highest in South-South Nigeria.

Many young men, unable to find stable work, are lured into cult groups with promises of quick cash, protection, and social identity. Cultism offers what society fails to provide — a sense of belonging and status, albeit through violence.

A local resident, who pleaded anonymity, said:

“Most of these boys joined cults because there’s nothing else for them. No jobs, no skills, and the streets became their only school.”

The absence of vocational centers, recreational spaces, and economic opportunities has created a breeding ground for criminal networks in Upper Sakponba and adjoining areas such as Ugbowo, Ekenwan, and New Benin.

Government and Security Response

The Edo State Government has repeatedly promised to restore peace in the area. In 2023, the Edo State Security Network (popularly known as Vigilante Edo) launched an operation to disarm cultists and arrest suspected leaders.

Governor Monday Okpebholo, in his recent SHINE Agenda policy, emphasized the need for improved community policing and youth empowerment as long-term solutions.

“We cannot arrest our way out of cultism,” he stated. “We must engage, reform, and reorient our young people with skills, mentorship, and hope.”

The Nigerian Police Force, Edo Command, has also increased patrols and set up joint task forces with local vigilante groups. However, residents say the measures often bring temporary calm — the violence resurfaces within weeks.

Analysts argue that without addressing the root causes of poverty and unemployment, the cycle of cultism will persist, regardless of how many arrests are made.

The Human Cost of Cult Violence

The emotional and economic toll of cult clashes is devastating. Families have fled their homes, traders have lost businesses, and landlords struggle to rent properties in “red zones.”

Between 2020 and 2025, community leaders estimate that over 300 people have died from cult-related violence in Benin City — a figure unconfirmed by official police reports but consistent with media investigations.

A widow, identified simply as Mama Joy, recounted her loss:

“My only son was shot by cult boys because he refused to join them. Since then, I’ve been living in fear. Every evening, I pray for night to pass without hearing gunshots.”

Beyond human casualties, the violence has eroded public trust in government institutions, making residents skeptical of both law enforcement and local politicians.

Community Efforts and Possible Solutions

Despite the grim picture, local community groups are rising to confront the menace. Churches, traditional rulers, and NGOs are organizing peace dialogues, youth sensitization campaigns, and vocational training programs to redirect idle youths.

Civil society organizations in Edo have called for a multi-stakeholder approach involving the Ministry of Youths, Education, and Security to design a unified anti-cultism framework.

Experts recommend:

-

Skill acquisition programs for at-risk youth

-

Community-based surveillance networks

-

Public education campaigns on the dangers of cultism

-

Support systems for victims and reformed cult members

Conclusion

The story of Upper Sakponba is not just about violence — it’s a mirror reflecting the broader challenges facing Edo State. Cultism, unemployment, and failed social structures are interconnected issues demanding coordinated responses from both government and citizens.

For true peace to return to Benin City, efforts must go beyond arrests and slogans. The fight must focus on rebuilding hope, empowering youth, and restoring trust in governance. Until then, the cries of families in Upper Sakponba will continue to echo as a haunting reminder of a city’s unfinished struggle for peace.

Leave a Reply